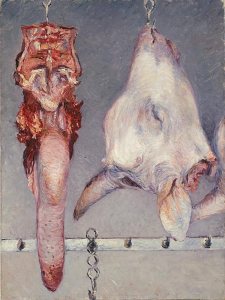

In the cooking and eating of #446 Lincolnshire Chine I have now ticked off all 17 recipes (by my reckoning) in the Cured Meats section of the Meat, Poultry & Game chapter of Jane Grigson’s English Food. The recipes contained within it were key in developing my own skills in traditional cooking and I acquired skills I didn’t think I had in me: dry and wet curing, pressing, smoking, potting, etc. Aside from acquiring new skills, cooking the recipes really made me appreciate good food, properly made: proper ham, bacon and salted (corned) beef – foods that have now largely become diluted-down commodity products. The majority of the recipes are pork-based; it seems that Jane wasn’t keen on fresh pork (there are just 2 recipes in her Pork section that use fresh pork joints) but finds pork products delicious. I must say I’ve never been that keen on roast pork myself, I’d much rather have a glazed ham!

In English Food, Jane opines on how ‘bacon was once our passion’ but is now outsourced to the Danish who turned pig farming into a real industry well before British farmers. As a country that in general prefers cheapness over quality, often discounting false economies, means that bacon filled with brine and injected with smoke flavouring has become the norm. So many of us have never eaten proper dry-cured butcher’s bacon, and I am glad to have been educated so well by Jane in the preparation of these foods that are considered very British – and the bacon sarnie is certainly one of those foods! And it’s not just a ‘cheerio’ to shrinking, scummy bacon: it’s a big ‘see you later’ to gammon and ham made from reformed offcuts, similarly injected with brine and additives.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce and would to start a £3 monthly subscription, or would like to treat me to virtual coffee or pint: follow this link for more information. Thank you.

We’ve forgotten just how important cured meats used to be to households all across the country. When autumn began to wane, all livestock, except for the breeding stock, were killed: of course, some fresh meat was eaten straight away, usually the offal because it didn’t keep and couldn’t be cured as well as meat from the carcass, which was salted down and eaten throughout the winter – this is why bacon was our passion. For many households, this meant ploughing through a great deal of bacon, gammon and ham, but beef was salted too, as was duck and even lamb and mutton. Salt beef was extremely important to the crews of sailing ships on long voyages: a sure way of providing protein to hardworking sailors.

I remember putting off any of the curing for a good while, fearing it slightly, but eventually I had to put my trust in Jane and her instructions. Of course, everything worked. Whenever things went awry, it was due more to my naivety than anything: for example, I used joints that were far too small to poach successfully; luckily I now know to cook as large a piece as possible, and pot what isn’t eaten in the next couple of days. Jane also taught me the importance of aromatics: cures are not simple brines, but they are flavoured with dark brown sugar, juniper, bay, allspice and nutmeg (to name but a few). The only thing I haven’t taken with me is the liberal use of saltpetre. Also going by the name potassium nitrate, saltpetre cures meat well and also gives the meat a nice pink colour, but there are associations with whole a host of diet-based diseases, so these days I miss it out. I don’t mind my bacon being a little less pink.[1]

One of the most fun elements of this chapter was potting: there were simple ones like #205 Potted Tongue, more complex ones like Elizabeth Raffald’s #434 To Pot Ham with Chicken, and then Hannah’s Glasse’s #366 A Fine Way to Pot a Tongue: a whole pickled and poached ox tongue stuffed into a boned chicken, immersed in spiced butted and baked. Glorious stuff.

One of the best recipes didn’t use cured meat: #375 Boiled Silverside of Beef (not boiled, but gently poached) was sublime, cooked with vegetables and eaten with horseradish. If you can spare the time and resources, I recommend #441 Smoking Meat (the only 10/10 score) and attempting the aforementioned potted tongue by Hannah Glasse (9.5/10). The most revisited recipes are Jane’s #150 How to Cure Meat in Brine, and #228 Spiced Salt Beef – the latter being very good indeed, and which makes a delicious potted beef; something I used to sell on my market stall right at the beginning of my career in food.

As usual, when I complete a part of the book I give you the stats for the section.[2] Cured Meat scored a mean of 7.53, putting it on level pegging with Pork and Poultry. The median score was 8, and there were two modes: 7 and 8.5. The only significantly better scoring section of the Meat, Poultry and Game chapter thus far is the section on Meat Pies and Puddings.

Below, I have listed the recipes in the order they appear in the book with links to my posts with their individual scores, so have a gander. It is worth pointing out, that my posts are no substitute for Jane’s wonderful writing, so if you don’t own a copy of English Food, I suggest you get yourself one.

#212 Bradenham Ham8.5/10

#150 How To Cure Meat in Brine 8/10

#151 To Cook Salt Pork and Hams 1: To Eat Hot 7/10

#265 To Cook Salt Pork and Hams 2: To Eat Cold 7.5/10

#441 Smoking Meat10/10

#161 Boiled Beef and Dumplings 8/10

#375 Boiled Silverside of Beef 8/10

#202 Pressed Beef 8.5/10

#228 Spiced Salt Beef8.5/10

#258 Boiled Ox Tongue 1: To Serve Cold 5/10

#331 Boiled Ox Tongue 2: To Serve Hot8.5/10

#205 Potted Tongue 4/10

#434 To Pot Ham with Chicken7/10

#366 A Fine Way to Pot a Tongue 9/10

#296 Tongue and Mushroom Crumble 6.5/10

#292 Isle of Man Salt Duck7/10

[1] Correlation is not necessarily causation of course. If you want to know more, I wrote about it on the other blog a while back. Read that post here.

[2] Is anyone interested except me?