This is a recipe that has been put off simply because I thought that it had to be served with the (#441) Smoked Chicken with Three-Melon Salad. Once I finally made the smoked chicken and was ready to make this one, I spotted that Jane actually wrote a ‘good accompaniment to smoked chicken, roast duck or lamb…’, so I could have cooked it ages ago. It’s a vegetarian recipe, but appears in the Poultry section of the Meat, Poultry and Game chapter, which is disappointing because it’s the final poultry recipe in the book, so a bit of a damp squib.

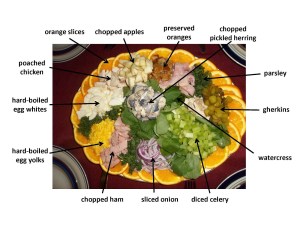

I’ve had mixed feelings about this recipe to be honest; I have a great dislike of pointless garnishes. Some foods just don’t need them. Chopped parsley is good with most British foods – but not all – and don’t get me started on the mint spring on a dessert, or as someone pointed out on Twitter recently, the single physalis fruit. Some foods are best on their own. What’s putting me off with this recipe is that it runs the risk of being a big, pointless faff.

One good thing, however, is that it introduces us a new ingredient, the bitter gourd – also known as bitter melon – those knobbly verdant green torpedoes you see in Asian grocery stores. Jane is surprised they are not used more often seeing as we have been a nation of Indian food lovers since the eighteenth century. Why hasn’t the nation taken to this delicious vegetable? Jane reckons it’s the bitterness: ‘Europeans’, she says ‘are not skilful with bitterness in food though we take it well enough in drink.’ Well, I’m game for something bitter.

The other two gourds are the more familiar courgette and cucumber.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this post for more information.

Gourd #1: bitter gourds

You need four small to medium bitter gourds here. Begin by removing sharp the knobbly edges with a vegetable peeler. Halve them lengthways and deseed, taking any pith away at the same time. Keep a couple of teaspoons of the seeds for later. Slice very thinly, place in a bowl with a good, heaped teaspoon of salt. Leave around three hours before rinsing and blanching in boiling water for three minutes. Fry the slices in about a tablespoon of butter to just soften for two or three minutes. Season with pepper, they may not need salt. Place in a pile on a warmed serving plate.

Gourd #2: courgettes

Jane asks for 10 to 12 small courgettes. If you can’t find small ones, then buy the equivalent in regular ones. I guessed at three. If you can find small ones, halve them, if they’re a bit bigger quarter them lengthways and in half crossways. Fry them gently in a tablespoon of butter and a small, finely chopped clove of garlic (we are looking for a suspicion of garlic here). Season with black pepper. Place the courgettes in a pile beside the bitter gourds.

Gourd #3: cucumber

Peel and thinly slice half a cucumber and fry gently in butter to just soften – two or three minutes is all you need. Pile up on the dish.

Increase the heat add a little more butter and cook through the reserved bitter seeds with a tablespoon each of parsley, coriander and chives. Cook for two minutes more and then scatter over the cooked gourds.

#442 Three-Gourd Garnish. Okay; what to say about this one? Well, the cucumber and courgettes were okay, and I like the herb combination. BUT the bitter gourds were so fantastically bitter they were totally inedible. There is only one way they could be used, in my opinion, and that’s very sparingly mixed in with the cucumbers, and by sparingly, I mean just a dozen or so thin slices. What I’m saying, I suppose, is a two-gourd garnish would have been bland, but at least you could have eaten it all. No thank you Jane. Unnecessary mint sprig: all is forgiven 3/10.