With finally cooking recipe #445 To Make a Yorkshire Christmas Pye, I have completed the Meat Pies & Puddings section of the Meat, Poultry & Game chapter of English Food by Jane Grigson.

It was quite a big section – 21 recipes in all – and because the English have a rich history regarding pies and puddings, it covers quite a lot of ground. I found Jane’s choices really evocative of both history and regionality, both of which have declined over this – and the last – century.

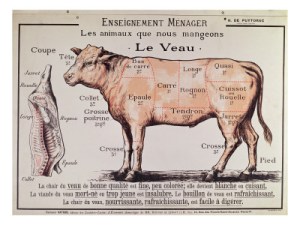

Of course meat pies have a chequered past, and factory-made ones with their homogenous pink insides, or their non-specific minced meats, have sadly become the norm for us Brits; but once every home had their own repertoire of meat pies and puddings, and perhaps popped into their butcher or grocer for special pies for special occasions. Jane pines for times past: ‘We were once known for our pork pies’, she says, ‘and other pies as well. Pies, like puddings, were a great English speciality. I suppose that the reason for our modern failure is that our butchery trade was not stiffened by the same legal props and alliances: with the increasing demand for cheap food, cheapness rather than quality, all professional skill has gone.’ They were so prized that folk owned special leather pie cases used for storing and protecting pies over long journeys. Jane also blames modern farming methods that have left us with pork that’s ‘had the succulence bred out of it.’

The historical ground she covers is amazing: and the English medieval raised pie receives plenty of deserved attention. There are the celebration pies of the 18th and 19th centuries, and includes Hannah Glasse’s #322 To Make a Goose Pye and #445 To Make a Yorkshire Christmas Pye. From medieval to Tudor times when pastry is a more delicate and pies are made from shortcrust pastry we have the classic #70 Cornish Pasty, designed to be held and tough enough to slip into a worker’s pocket to survive a morning’s work. Then, as we move into the Stuart era, pastry get even more rich and ‘puff pastes’ begin to appear, perhaps to top your #43 English Game Pie. All types are in there, and I have to say I have come quite adept at almost every aspect of pie and pastry-making, right down to the #283 Jellied Stock.

Jane had her own thoughts on pastry, bringing up ‘the question of taste and discretion. If you make a Cornish pasty for a miner…the pastry has to be very thick, or the whole thing will spoil. If you are making mince pes for the end of as large meal, you will need to roll the pastry thinner than if they are destined to fill up hungry young carol singers.’ Therefore she gives little information on how much pastry required, or indeed how to make it – something one would not get away with today. She says: ‘This is the kind of cooking accommodation we rapidly become used to. Therefore…only the type of pastry will be indicated, not its weight.’ I must admit I agree; after you’ve made a couple using your own dishes, you do get an instinct for how much you may need.

I have to say I got so much pleasure from cooking these recipes, especially the raised pies. Indeed it was making these pies in the US in my science days, and seeing how well they went down with folk who do not have them as part of their food culture, stirred up thoughts of starting my own food business. Years later I would become known for my pies making them in their hundreds for the restaurant. I have much to thank Jane for.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

There are many recipes that are not included in the chapter, but I suppose Jane had to stop somewhere, there being thousands of pie and pudding recipes. But some omissions are glaring: my main issue being the lack of puddings – one recipe in the whole section! If there is anything more English than a meat pie, then it is meat pudding. To be fair the one she does include – #200 Steak, Kidney & Oyster Pudding – is the classic, but I would have added maybe minted lamb, oxtail and plough pudding at the very least. Her niche, regional pies were interesting, but not always a success. If I were to write a pie chapter I would certainly add beef & potato, minced beef & onion and a proper pigeon pie of old: pigeon, beefsteak and bacon baked in a double layer of suet and shortcrust pastry.

There were some very, very good recipes: #43 English Game Pie (hot, with puff pastry) and #369 Game, Chicken or Rabbit Pie (cold, with hot water pastry)both scored full marks, and the excellent potato-topped #416 Cumbrian Tatie Pot narrowly missed out with a score of 9.5/10. Then, #320 Steak, Kidney and Oyster Pie and its pudding equivalent (#200) both scored 9/10.

I have to give a special mention to the showstopping pyes from Hannah Glasse: #445 To Make a Yorkshire Christmas Pye being possibly the craziest thing I’ve ever made in my life.

#156 Cheshire Pork and Apple Pie was the only disappointing one really.

Time for the stats: there were 21 recipes, but I only counted 18: #282 Raised Pies and #283 Jellied Stock being constituents of other recipes, and the Christmas pye which I never got to eat.

The section scored a mean of 8.11/10, the second-highest score so far (9.1 Stuffings being the highest). It has a median and mode of 8 – high, but others have been higher measured this way.

As usual, I have listed the recipes below in the order they appear in the book with links to my posts and their individual scores, so have a gander. It is worth pointing out, that my posts are no substitute for Jane’s wonderful writing, so if you don’t own a copy of English Food, I suggest you get yourself one.

#70 Cornish Pasty 8/10

#320 Steak, Kidney and Oyster Pie 9/10

#129 Dartmouth Pie 7.5/10

#233 Devonshire Squab Pie 6/10

#416 Cumbrian Tatie Pot 9.5/10

#388 Sweet Lamb Pie from Westmorland 8/10

#156 Cheshire Pork and Apple Pie 5/10

#303 Cornish Charter Pie 8.5/10

#209 Chicken and Leek Pie from Wales 7/10

#324 Rabbit Pie 8/10

#43 English Game Pie 10/10

#214 Venison (or Game) Pie or Pasty 7.5/10

#282 Raised Pies n/a

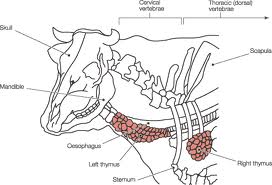

#284 Veal, Ham and Egg Pie 8.5/10

#369 Game, Chicken or Rabbit Pie 10/10

#445 To Make a Yorkshire Christmas Pye (Part 1 & Part 2) ?/10

#322 To Make a Goose Pye 8.5/10