Here’s the second of the two recipes in English Food that uses primitive lamb. Regular followers will know that I acquired two legs of Hebridean hogget earlier this year. A hogget is a sheep that’s too old to be lamb, but not yet considered mutton. It was wonderful to go to the farm and chat with Helen, the farmer who works so hard to keep this rare and primitive breed alive and kicking. Here’s the episode of my Lent podcast that included my interview with her :

Primitive breeds such as the Hebridean need help: help from specialist farmers and help from us, because they won’t survive if there is no demand. Primitive breeds are excellent for the smallholder – they are small and easy lambers, meaning their husbandry is much less stressful than large commercial breeds with their giant lambs! They have great character too: they are brighter and are excellent foragers that display more natural behaviours. If I ever get a bit of land, I will definitely be getting myself a little flock.

In that episode we focus on the one breed, but I thought I’d give a mention to the other primitive breeds just in case you are thinking about getting hold of some. Aside from the Hebridean there are the Soay, Manx Loaghtan, Shetland, Boreray and North Ronaldsay. They all belong to the Northern European short-tailed group, and they were probably brought to the Outer Hebridean islands by Norse settlers. They are small, very woolly and extremely hardy sheep. The islands upon which they were found were the St Kilda archipelago, and had been there since the Iron Age. Some moved and adapted, the Manx Loaghtan obviously went to the Isle of Man, but some remained on the islands and adapted too. The North Ronaldsay, for example, lives on the small rocky northernmost islands and has become a seaweed-grazing specialist.

Of all the breeds, the Soay sheep are considered to be the most like their ancestors, and it is found on several islands in the archipelago. On the island of Herta, a feral population of around 1500 was discovered; their name is befitting because Soay is Norse for sheep island.

This recipe is exactly the same as the other one except the lamb is served with a blueberry sauce rather than a gravy. Although we are at the tail-end of the blog, I actually made this sauce for my first ever pop up restaurant all the way back in 2013 which took place in my little terraced house – a lot has happened since then, that’s for sure! It sounded so delicious I couldn’t wait until I found some primitive lamb. The usual fruit to serve with lamb is of course the tart redcurrant, usually in jelly form. Blueberries are usually sweeter than currants, but Jane is not daft and makes up for it with the addition of a vinegar syrup.

And, if you are thinking this is some kind of American abomination, don’t be so sure: although all of the blueberries we buy in shops are undoubtably American varieties, don’t forget its close relative, the more humble blaeberry, which I suspect is what the lamb would have been served with. It’s appeared in the blog before, and scored full marks: #xxx Blaeberry Pie

Anyway, enough waffle: here’s what to do:

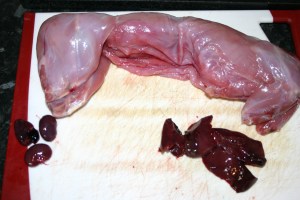

Roast the lamb or hogget as described for #438 Plain Roast Primitive Lamb with Gravy, but instead of making the gravy start to make this blueberry sauce as it roasts:

In a saucepan simmer eight ounces of blueberries with ¼ pint of dry white wine, ¼ pint of lamb stock and a tablespoon of caster sugar. Remove a couple of dozen of the best berries for the garnish and blitz the remainder in a blender and pass through a sieve.

Dissolve 2 teaspoons of sugar in 6 tablespoons of white wine vinegar in a small saucepan and boil down until quite syrupy, then add to the blended berries along with some finely chopped mint or rosemary. Set aside and return to it when the roast had been taken out of the oven.

Skim any fat from the meat juices and pour them into the blueberry sauce. Reheat and add some lemon juice – I used a little shy of half a lemon here – and then season with salt and pepper, and even sugar if needed. When ready pour into a sauce boat, not forgetting to add in the reserved berries.

#440 Primitive Lamb with Blueberry Sauce. Well you won’t be surprised that this was, again, delicious, how could it not be? I did a better job of roasting it this time I feel. I really enjoyed the blueberry sauce and it went very well with the slightly gamey meat. I think I may have preferred the plain gravy to the blueberries though, but there’s not much in it. Because of this doubt, I am scoring it a very solid 9.5/10

P.S. The leftovers made an excellent #84 Shepherd’s Pie.

Refs:

‘British Rare & Traditional Sheep Breeds’ The Accidental Smallholder website: www.accidentalsmallholder.net/livestock/sheep/british-rare-and-traditional-sheep-breeds/

‘Soay’ RBST website www.rbst.org.uk/soay

‘Manx Loaghtan’ RBST website www.rbst.org.uk/manx-loaghtan

‘Hebridean Sheep Characteristics & Breeding Information’ Roy’s Farm website: www.roysfarm.com/hebridean-sheep

‘About Shetlands’ North American Shetland Sheepbreeders’ Association website: www.shetland-sheep.org/about-shetlands/

‘The Origins of Registered Boreray Sheep’, Sheep of St Kilda website: www.soayandboreraysheep.com/

‘Boreray’ RBST website: www.rbst.org.uk/boreray-sheep-25

‘North Ronaldsay’ RBST website: www.rbst.org.uk/north-ronaldsay