Hello there Grigsoners! No, I’ve not died, I have simply been a lazy bastard. I am going to stop apologising for my blog-tardiness and try my very best to pull my finger out. All that said, I have been preparing this recipe on the sly for the last few days. I went to Central Market with Gerda from the lab a while ago and found that quite alot of the ingredients that are tricky to get hold of in the UK are actually much easier to get hold of here in Texas. In the meat section, I happened upon an ox tongue and I knew that there are quite a few recipes using ox tongue specifically so I thought I’d grab it and do something with it later.

I decided upon this one – Boiled Ox Tongue: to Serve Cold, because I could take it into work and force my new labmates to eat it and (hopefully) put some comments on here! The recipe calls for a 2 ½ to 5 pound pickled (i.e. brined) ox tongue – these you can order form your butcher (in the UK at least). I thought I would pickle it myself using this now tried-and-tested brine method from English Food. The tongue needs 5 to 7 days in the brine tub, but there is no maximum time really – you can’t oversalt anything, because you can soak it in water for 6 or so hours beforehand. It’s recommended you do this with a pickled tongue from the butcher’s shop.

|

| The tongue before brining |

Anyways, after you have soaked your tongue place in a stock pot and cover with cold water or a light stock. Bring it to the boil and skim any scum that appears at the water’s surface. Turn the heat down to the merest simmer. After half an hour, taste the water – if it is horribly salty, thrown the water away and start again. Add some stock vegetables: an onion studded with a couple of cloves and a chopped carrot and celery stick. Add also a bouquet garni and 12 crushed black peppercorns. Allow the whole thing to simmer for a total of 3 or 4 hours (don’t forget to include that first half hour!). The tongue is cooked when you can insert a skewer with ease.

|

| The pressed but unsliced tongue |

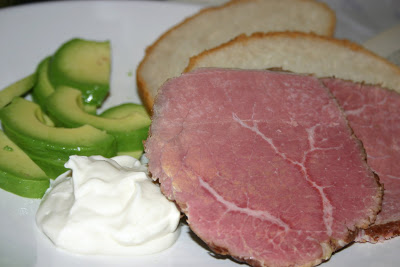

When you are ready to eat it, slice it thinly and serve with a salad and some horseradish sauce so says Lady Jane Griggers. If you want to be all Victorian about it ‘press the tongue into a slipper shape, and then decorate it with aspic jelly and bits and pieces’. However, The Grigson goes on to say: ‘I think we have lost sympathy with over-presented food of this kind: it always arouses my suspicious – I wonder what the caterer is trying to conceal.’