It’s been two years since I last posted a recipe on here! I can only apologise. This recipe really should have been cooked long ago. There were two reasons I put it off: First, according to Jane, the gargantuan joint feeds 10 to 12 people, and comes in at a weighty 9–12 lbs / 4 ½ -6 kilos. I have done many Jane Grigson-themed dinner parties in the past, but never one that could feed 12. That said, I did cook a saddle of lamb for my very first pop-up restaurant in 2013, but that was off the bone and dressed for easy carving. For this recipe, Jane insists upon bone-in. The second reason was that I assumed the cut she describes was too arcane. She tells us ‘[t]he butcher will have prepared the saddle by slitting the tail and curving it over, with the two kidneys between the tail pieces and the saddle.’ She goes on: ‘for this kind of high-class butchery it is wise to go to an experienced man of mature years and if his father was a butcher before him, so much the better.’

I asked several butchers, and they all thought it odd I was asking for a saddle on the bone, and none quite understood Jane’s description.

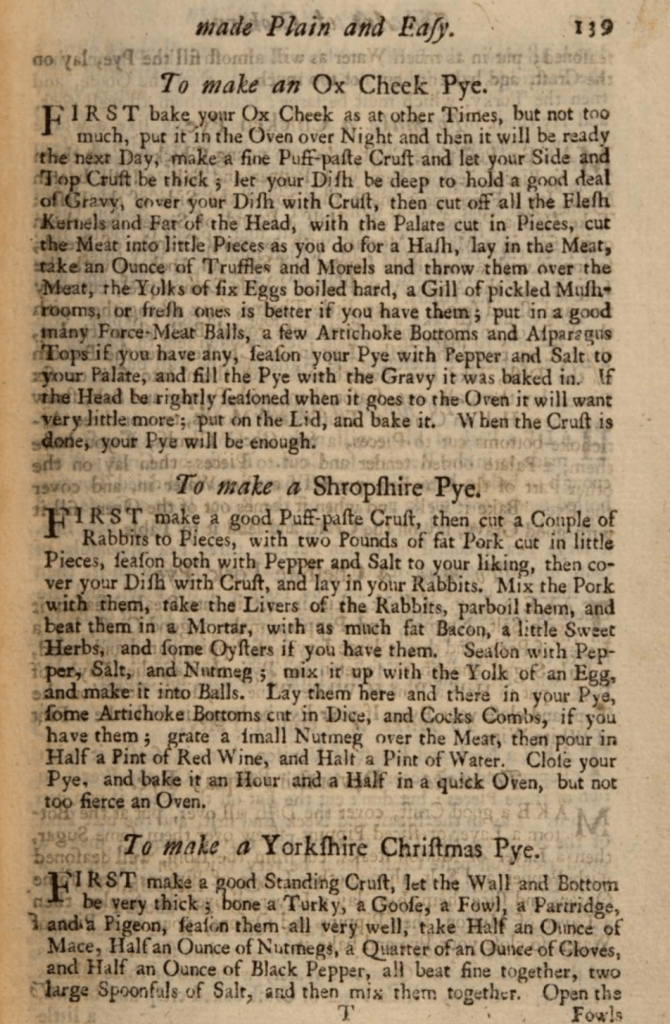

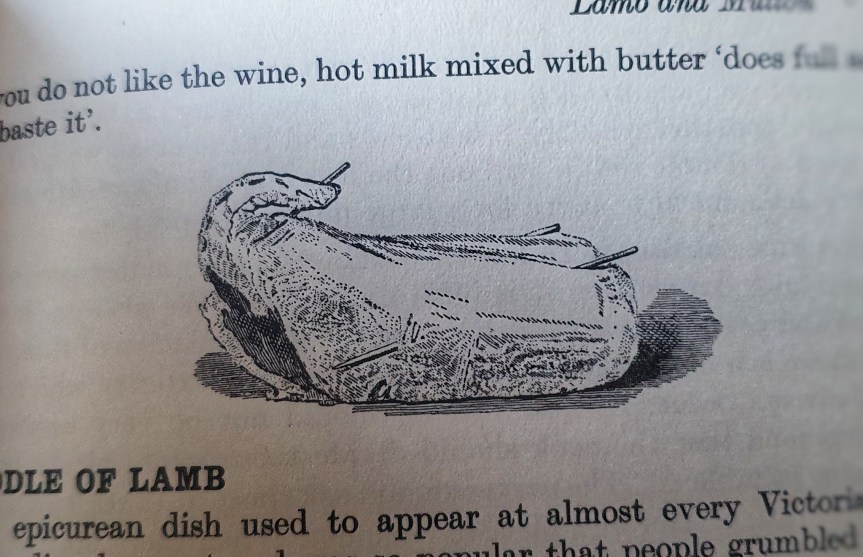

Frustrated that I couldn’t get a handle on Jane’s description, I hit the books. The Constance Spry Cookery Book (1956) tells us a saddle of lamb is made of the ‘two loins together from ribs to tail.’ Going back in time a few decades, Charles Francatelli (1907) describes no fewer than six recipes for saddle of lamb, all of which ask for a boned, rolled saddle. He does mention a baron of lamb made up of back, rumps and tops of legs, which seems too far the other way! Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861) doesn’t describe the joint, but it does tell us that ‘the joint is very much in vogue’. There is an illustration, but it is so small in my first edition transcription that it is of little use. Lastly, Eliza Acton, writing in 1845, provides a recipe but again provides no explanation of the meat itself – everyone is assuming we all know what a saddle of lamb should look like, it seems.

I settled upon ordering a saddle from Hopkinson’s of Lymm, a great butcher who talked me through the butchering process. The tail piece wasn’t there, but that’s okay. It would serve eight looking at it, and that was the number of folk I would be feeding, so I was very happy.

It was only after I had cooked the joint and started researching for this post that I found some more information, and it was with the pages of Sheila Hutchins’ English Recipes (1967) that I had a eureka moment, because there is a lovely, clear illustration of the joint. Rats! It’s always the way. She also tells us that ‘[t]his epicurean dish used to appear at almost every Victorian and Edwardian banquet’, but ‘inevitably’ became a middle-class aspiration.

Going by this new evidence, I was happy that my saddle was essentially a neatened and slightly over-trimmed version of the joint Jane wanted us to cook.

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

And so, I cooked the saddle for three Grigson dinner party stalwarts: Nic Alden, Simone Blagg and Anthea Craig. There were eight of us in all – a huge thank you to Simone for hosting the meal. My teeny flat couldn’t hold more than four people! Have a listen to this podcast episode about past Grigson dinner parties to hear us discussing the low and high points of parties past:

To roast the lamb, first preheat the oven to 190°C. Then, rub all over with salt, pepper and thyme leaves. If you like, insert thin slivers of garlic into the meat, and then brush it with a little melted butter.

Now I didn’t follow Jane’s exact cooking instructions because my joint was lighter than the one she described. If yours does weigh in at her size, roast it for 2½ hours, basting it with a quarter of a pint of port or red wine. Keep basting with the wine and juices every 30 minutes or so. Then, in the final 30 minutes, dredge it with a scattering of flour and dribble on a little more melted butter.

My joint weighed in at 2 kg, so I did the same as Jane describes, except for two things: because the joint wouldn’t be in the oven as long, I preheated it to 230°C, roasted it for twenty minutes, and then turned it down to 190°C, and roasted it for 1 ¼ hours. As it turned out, it was perhaps in the oven too long, because there was just the merest sign of pinkness. Sixty or sixty-five minutes would have been better to suit my tastes.

Remove the meat from the oven and keep warm as you prepare the gravy: make a roux by cooking an ounce of butter in a saucepan until it turns golden brown, then stir in a tablespoon of flour. Mix and cook the roux out for a few minutes, then pour in the cooking juices (skim away the fat first). Deglaze the roasting pan with ¾ pint of lamb stock – made either from the trimmings or from a good preparatory brand – and add to the gravy. Add the liquids in stages to avoid lumps. Season with salt and pepper. Strain into a gravy jug.

Carving the saddle was easy: I cut down the sides of the backbone and then the ribs, pulling away the carved meat with one hand, keeping it taut, making for easier cuts against the ribs. Then it was a simple case of slicing it up.

I also served it with Jane’s excellent blueberry sauce.

#447 Roast Saddle of Lamb. What a delicious piece of meat! I’ve cooked racks of lamb several times now, but roasting them in one large piece like this was quite something – one thing I have learned is that the tenderest roasts are made with the large pieces of meat. I heartily recommend roasting a saddle of lamb on the bone. The only issue was that I slightly overcooked it (to my taste at least). I therefore will knock off half a mark: 9.5/10.

References

Acton, E. (1845) Modern Cookery For Private Families. Quadrille.

Beeton, I. (1861) The Book of Household Management. Lightning Source.

Francatelli, C.E. (1906) The Modern Cook. Macmillan and Co. Ltd.

Grigson, J. (1992) English Food. Third Edit. Penguin.

Hutchins, S. (1967) English Recipes, and others from Scotland, Wales and Ireland as they appeared in eighteenth and nineteenth century cookery books and now devised for modern use. Cookery Book Club.

Spry, C. and Hume, R. (1956) The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Weidenfeld and Nicholson.